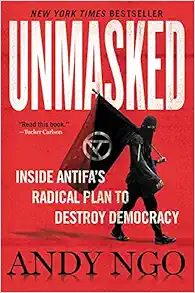

Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy,

Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy,

by Andy Ngo

Reviewed by Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

Antifa Galore

An intrepid investigative journalist Andy Ngo has written a shocking expose of America’s Antifa, or the “Anti-fascist” movement: Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy (New York and Nashville, TN, Center Street, 2021).

I should qualify this: it is shocking for a casual reader. For me, it is business as usual. Not only did I study its original paradigm in interwar Germany, but I also witnessed its modern-day iterations in Europe in our times.

According to Ngo, “antifa are an ideology and movement of radical pan-leftist politics whose adherents are mainly militant anarchist-communist or collectivist anarchists… Their defining characteristics are a militant opposition to free markets and the desire to destroy the United States and its institutions, culture, and history” (p. 8). The journalist stresses that “not all of its followers participate in violence. In fact, most don’t and instead work on delegitimizing liberal democracy and the nation-state through ‘charity’ and relentless propaganda” (p. 8).

The current avatar of Antifa in the United States is a highly-decentralized motley crew of anarchists, communists, and other violent revolutionaries. It lacks a national structure; instead, it is set up as a plethora of amorphous community organizations with clandestine structures of several levels, each requiring initiation.

Each cell is led by an informal, secretive hierarchy of community organizers. It is unclear whether a collective leadership principle applies in each structure or a single leader dominates. Probably it can be both, depending on a location and particular circumstances.

Ngo tells us that at least a few leaders keep in touch through electronic means and endeavor to coordinate some of their activities. The leaders can either mobilize their followers from above, most likely by prompting intermediaries, to action, or they can join and take over a pre-existing grassroots explosions and channel it into the desired direction. However, that is a question that the FBI should answer.

The Antifa dialectically takes advantage of the system. It parasites on it, including by getting taxpayer subsidies for its front organizations. “Despite claiming to be an ‘autonomous zone’, CHAZ [an Antifa-founded enclave in Seattle] was a welfare state parasitizing on Seattle taxpayers” (p. 42). Elsewhere, in Portland, for instance, money donated to “the cause” and “charity” is embezzled, and Antifa community organizers disappear without a trace (p. 56).

The organization’s tactics are purely revolutionary. This includes arson attacks on state and other infrastructure, including charitable organizations and others like St. Andre Bessette Catholic Church in Portland (p. 76). According to Ngo, “Antifa know the effect that smashed windows, breached businesses, and fires have on crowd mentality. Each act serves as blood in the water. It can turn protesters into rioters. That’s why antifa teach this in their literature that is disseminated widely online and in real life” (p. 16).

Nevertheless, at this stage, Antifa makes an effort to dial down violence. It stops short of killing. “The plan now is to create a decentralized system of cells and affinity groups who share in the same ideology through disseminated propaganda and literature. They recognize the accelerationist tactics like mass killings of police or political opponents are too high risk. The goal is to inflict maximum damage without death and to maintain the momentum of riots to drain government resources and law enforcement morale” (p. 156).

Of course, it does not mean that the revolutionaries do not kill at all. From time to time, they slaughter and rejoice at their deeds. Following the killing of a conservative pedestrian, Aaron Danielson, in Portland in August 2020, “they celebrated his death through dancing, song, and the burning of American flags” (p. 183).

Paradoxically, Antifa is decentralized similarly to America’s neo-Nazi, racist, white supremacist, and other extremist movements. Further, Antifa’s plan for the destruction of democracy and the United States follows the script laid out in an anti-liberal novel, The Turner Diaries (1978): a decentralized convergence of mass demonstrations and attacks by revolutionaries on the centers of power, culminating in the takeover of Washington, DC. I believe Andy Ngo has largely overlooked the connection.

Ngo calls Antifa “a phantom movement by design” (p. 18). “This is the phantom cell structure of antifa that makes them analogous to global jihadism. A unifying ideology and political agenda ties together individuals, cells, and groups” (p. 84). He also traces its origins to Sweden, at least in their Portland stronghold (pp. 82-83).

Its decentralization notwithstanding, its activists style themselves as the fist of the international revolution driven by “critical theory,” “intersectionality,” “class struggle,” race struggle, and ‘sexual radicalism (pp. 83-95). They advocate violence (or a “calibrated level of violence,” p. 64), including property destruction because property derives from “whiteness.” Looting and burning challenge thus “white supremacy” (p. 126). They also hate American patriotism: “On August 4, 2018, antifa black bloc militants beat a leftist ally at one of their protests using a spring-loaded club. Why? Paul Welch made the mistake of carrying an American flag” (p. 153).

According to Ngo, “American antifa has the communist and anarchist origins of European antifa, but it has evolved to include contemporary social-justice politics from critical theory. Intersectionality flows through American antifa. The revolution they are fighting for will not be led by workers but rather trans, black, and indigenous ‘folx’ of color” (p. 127).

The Antifa works closely with Black Lives Matter (BLM), which likewise opposes “free speech” and aims at “abolishing law enforcement, American jurisprudence, national borders, and free markets in the name of anti-racism and anti-fascism” (p. 129).

Since most Antifa activists seem white, one should ponder the uncanny resemblance of their propositions to the “Helter Skelter” ideology of Charlie Manson from the 1960s. This convicted murderer and sectarian judged the blacks and other minorities to be mentally unfit to lead a revolution and, hence, he offered his services as a leader.

At any rate, the American Antifa revolutionaries invoke Michel Foucault and Herbert Marcuse along with his stricture, in the name of tolerance, not to tolerate those who disagree with the revolutionaries (pp. 24-25). Thus, they are firmly versed in the leftist intellectual offerings of contemporary times.

Their modus operandi is straightforward: “If antifa’s operationalized tactics can be described as a multi-prong machine working through violent and nonviolent means, the lubricant keeping it all going is information warfare. A military concept, information warfare refers to the use, denial, exploitation, or manipulation of information against an opponent. That includes hiding information as well as spreading disinformation and propaganda to wage war. And no one does [better] propaganda for antifa than sympathetic journalists and useful idiots” (p. 210).

A case in point is the baseless accusations of Nazism levied against Marine veteran Justin Gaertner, who lost both legs in combat in Afghanistan, by the Antifa-sympathizing Ivy Leaguer Talia Lavin, a former employee of The New Yorker Magazine (p. 216). The false smear paved the way for the employment of Talia as a journalism professor at New York University in 2019.

Unlike Ngo, I have studied both sides of the coin: Antifa and anti-Antifa. Both tend to be revolutionary phenomena of the left, except that a minority splinter of the latter can be counterrevolutionary, firmly embedded on the right. Please bear with me as I explicate because Ngo’s grasp of the movement’s roots is his weakest spot (pp. 99-102).

The original Antifa emerged from the street violence of the 1920s and 1930s in Weimar, Germany. Initially, it was a multipronged battle pitting various orientations against each other. Each leftist group had its own separate fighting militia. The rightists responded in kind by fielding highly de-centralized veterans’ outfits – the Freikorps.

The monarchist and conservative Stahlhelm (Steel Helmet) were the weakest. It duked it out with all others, but – like the liberals and most progressives – the right-wingers increasingly came to rely on the police and the army to reign in the leftists.

The latter were revolutionaries: anarchists, international socialists, and national socialists (Nazis). For the longest time, Moscow ordered its Communist fighting squads of the Rot Front (Red Front) to crush not just the Nazis but also socialist and anarchist militias.

It was a free for all on Germany’s streets. Whoever won the day attracted goons from other fighting groups. So the Nazis joined the Communists and vice versa; the socialists and anarchists fluctuated as well.

In the early 1930s, scared by Hitler, Stalin changed tack. A “Popular Front” came into existence in Germany, with Antifa as its leading fighting group. It was harnessed by the Komintern, the Soviet secret police, and their Willi Münzenberg deception machine, which eulogized the revolutionary thugs as “freedom fighters.”

By then, it was too late. The Nazis won power. Yet, the legend of the Antifa and the Popular Front lived on.

Before the recent Time of Troubles in the United States, hardly anyone had heard about Antifa. They tended to stew in their own sauce; they stayed away. The Old Continent is relatively small; even a casual passerby would notice their traces, in urban areas in particular.

In London in the summer of 1980, I observed two adversarial youth subcultures, the skinheads and the punks. Modern-day Antifa harkens from the latter. Oddly, its contemporary American iteration also includes sports fans, while European soccer hooligans tend to stand on the opposite side.

Naturally, there were exceptions, for instance, Skin Heads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP). Dressed identically as other skinhead crews, they were virtually indistinguishable from their opponents as they brawled violently with them. Unlike SHARP, their adversaries hated Israel and the Jewish people while eulogizing the Palestinians. That has now changed as Antifa oozes scorn at Israel and touts its “anti-Zionism” as a badge of honor.

All that I found out only in the early 1990s when I was back in the United Kingdom. I further remember the French scene. In particular, I recall vividly when, on January 21, 1993, to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the murder of King Louis XVI by the revolutionaries, monarchist and Christian nationalist kids took over the Panthéon in Paris.

This used to be the Church of Saint Genevieve, which the French revolutionaries desecrated and turned into a mausoleum to celebrate their own secular saints.

Some hard-core extremists from the United Right Group (Groupe Union Droit – GUD) joined the occupiers, further reinforced by royalist youth and other assorted sympathizers from Spain. The police failed to dislodge them. The demonstrators agreed to leave the Panthéon under safe-conduct, and that is when the cops beat them up. Assorted Trotskyites and other proto-Antifa types later set upon the scattered remnant.

I saw Antifa casually swaggering in Cophenhagen several times. In the mid-1990s in Berlin, while visiting family friends, I heard complaints about Antifa routinely attacking police officers, taking over private properties for squats, and burning cars.

In 2014, I witnessed Antifa types hanging out with Middle Eastern types in Vienna, wearing “Arafat” scarves in solidarity with Palestinians. Their squat was marked with “Bourgie raus!” (Middle class, out!) graffiti.

In 2011, a visiting Berlin Antifa crew in Warsaw attacked Napoleonic wars reenactors, who marched in Poland’s Independence Day parade. They were chased away. Within a few years, indigenous Polish Antifa groups appeared. They specialize in violent attacks against patriotic marchers and abortion opponents, for instance, assaulting the latter with a hammer in 2020.

So much for Antifa’s propaganda of “terrorism without violence.” In fact, “driven by intense hatred, antifa want their targets to fear living a normal life” (p. 197).

Generally, Antifa would be a minor problem if it were not for liberal encouragement and protection. We should target the liberal enablers. This includes not only notorious organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center, which should have its tax-exempt status yanked for countenancing revolutionary terrorism.

We should also bring to account liberal and progressive politicians, district attorneys, and county, state, and federal prosecutors and judges, who go easy on Antifa terrorists. Also, we should consider improving our chances to neutralize and persecute Antifa activists. We should deploy drones against them for surveillance during demonstrations and riots and undertake infiltration of their structures by law enforcement at all levels.

The Antifa thugs count for little without their liberal protectors.

Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy is for the ordinary people who need to wake up. “If one isn’t tuned to the nuances of the American political and culture war, for example, people like my own parents, the default position is to view antifa as the ‘good guys.’ With the obligations of family life and work, few have time to actually investigate beyond the headlines and leading paragraphs” (p. 211).

We in America owe Andy Ngo a debt of gratitude. I wish more kids of the Vietnamese immigrants were more like him (and I met some of their parents who were so while with the Amnesty International at UC Berkeley in the 1980s under the tutelage of my boss, Sister Laola Hironaka, who was the first, already in 1979, to popularize the plight of the Vietnamese “boat people” – and not Ginetta Sagan and Stephen Denney in 1982 as Ngo believes, (p. 226) – or more like Cuban-Americans, still squarely on the anti-Communist side of history.

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

Washington, DC, 3 December 2021

Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy,

Unmasked: Inside Antifa’s Radical Plan to Destroy Democracy,